DEMOCRACY AND MENTAL HEALTH:

THE IDEA OF POSTPSYCHIATRY

PAT BRACKEN

(This Chapter is based on a BMJ article by myself and Dr. Phil Thomas, see Bracken and Thomas (2001)

INTRODUCTION

The 20th century is often held up as the great era of democracy. There were clearly many important struggles and successes. Women achieved the right to vote for the first time in many countries and colonial rule came to an end in different parts of the world. But democracy is about something greater than politics and parliaments: to me democracy is about ordinary people having control of their lives and this is a bigger issue than who is allowed to vote; when, where and for whom.

When it comes to controlling our own lives and destinies it is clear that in the past fifty years various types of technology have begun to dominate the ways in which we work, the ways in which we communicate with one another, how we travel and what we do with our leisure, in short how we live our lives. But let us be clear: technology is not just about machines and gadgets, computers and mobile phones, it is also about systems of knowledge and expertise. It concerns ways of ordering our reality and, increasingly, ordering our relationships.

In fact, I would suggest that one of the greatest expansions of technology has been in the world of mental health. As we begin the 21st century we have a huge (and growing) pharmaceutical industry, one branch of which is dedicated to the production of various chemicals to control our thoughts and emotions. We have an array of different machines to scan our brains for different types of activity. But the expansion of psychiatric technology has been in other directions as well: alongside the various psychodynamic therapies we now have cognitive-behavioural therapies and various systems of family intervention. We have numerous 'tools' to assess personality, to assess motivation and compliance and of course to assess something called 'risk'.

If democracy is about ordinary people controlling their lives, the question arises as to whose knowledge lies behind these developments? What assumptions guide the theories and practice of psychiatry and its associated therapies? Are these assumptions valid? Could we, should we, work with different assumptions, with a different set of priorities? I believe that the struggle for democracy is not something which belongs to the last century but is very much on the agenda now and nowhere more so than in our area of mental health. In my opinion, we need a genuine, open and democratic debate about mental health. Users, carers, lay people and mental-health workers need to take control. At present we have a very narrow discussion about what is helpful and of value. The parameters of this discussion are set largely by corporate (mainly pharmaceutical) and professional interests.

Postpsychiatry is about creating a space in which a new debate can take place. In this chapter, I shall first discuss what I regard as the key guiding assumptions of 20th century psychiatry. I shall then point to some reasons why these assumptions need to be challenged and I then write about postpsychiatry as a new, and positive, direction for mental health work.

MODERNIST PSYCHIATRY

Both critics and supporters of psychiatry agree that, historically, modern psychiatry is very much a product of the European Enlightenment. Prior to the Enlightenment, or the Age of Reason as it is also called, the concept of mental illness as a separate area of medical endeavour simply did not exist: there were no psychiatrists or psychiatric patients as such. It is only with the intellectual and cultural developments of the age of reason that we see a field of medical work open up which eventually becomes psychiatry.

The age of reason is difficult to define and to locate historically. However, beginning in the mid-17th century it is clear that there was a major shift in the cultures of Europe. It is impossible to say exactly why the Enlightenment began and why it developed as it did. Some historians argue that it began with the rise of science, others with the rise of capitalism. Other factors were the emerging bureaucracy in most European states and the fact of colonialism and increasing literacy. However, these influences weren't unidirectional, the assumptions which were at stake in the Enlightenment also fed into these developments.

Enlightenment meant a turn towards the light: the light of reason. There was a turn away from a focus on religious revelation and the wisdom of the ancient world and towards science and rationality as the path towards truth and progress. On a practical level, with its focus on reason and order, the Enlightenment spawned an era in which society sought to rid itself of all 'unreasonable' elements. As the historian Roy Porter writes:

"And the enterprise of the age of reason, gaining authority from the mid-seventeenth century onwards, was to criticize, condemn and crush whatever its protagonists considered to be foolish or unreasonable. All beliefs and practices which appeared ignorant, primitive, childish or useless came to be readily dismissed as idiotic or insane, evidently the products of stupid thought-processes, or delusion and daydream. And all that was so labelled could be deemed inimical to society or the state - indeed could be regarded as a menace to the proper workings of an orderly, efficient, progressive, rational society" (Porter, 1987, pgs 14-15)

According to Michel Foucault (1967), the emergence of the institutions in which 'unreasonable' people were to be housed was not in itself a 'progressive', or medical, venture. It was simply, and crudely, an act of social exclusion. He coined the term 'The Great Confinement'. Furthermore, he argued that it was only when such people had been both excluded and brought together that they became subject to the 'gaze' of medicine. According to Foucault, Porter and other historians, doctors were originally involved in these institutions in order to treat physical illness and to offer moral guidance. They were not there as experts in disorders of the mind. As time went on, the medical profession came to dominate in these institutions and doctors began to order and classify the inmates in more systematic ways. Roy Porter writes :

"Indeed, the rise of psychological medicine was more the consequence than the cause of the rise of the insane asylum. Psychiatry could flourish once, but not before, large numbers of inmates were crowded into asylums" (Porter, 1987, pg 17).

Medical superintendents of asylums gradually became psychiatrists, but they did not start out as such. Alongside the dominance of psychiatrists, the concept of mental illness became accepted. In other words, in this account, the profession of psychiatry and its associated technologies of diagnosis and treatment only became possible in the institutional arena opened up by an original act of social rejection.

The Enlightenment was also concerned with an exploration of the individual self. The romantic poets began to explore the imagination and playwrights and novelists began to focus on personality and character, not just on plot. This concern with subjectivity was also seen in philosophy and in the early part of the 20th century gave rise to the disciplines of phenomenology and psychoanalysis.

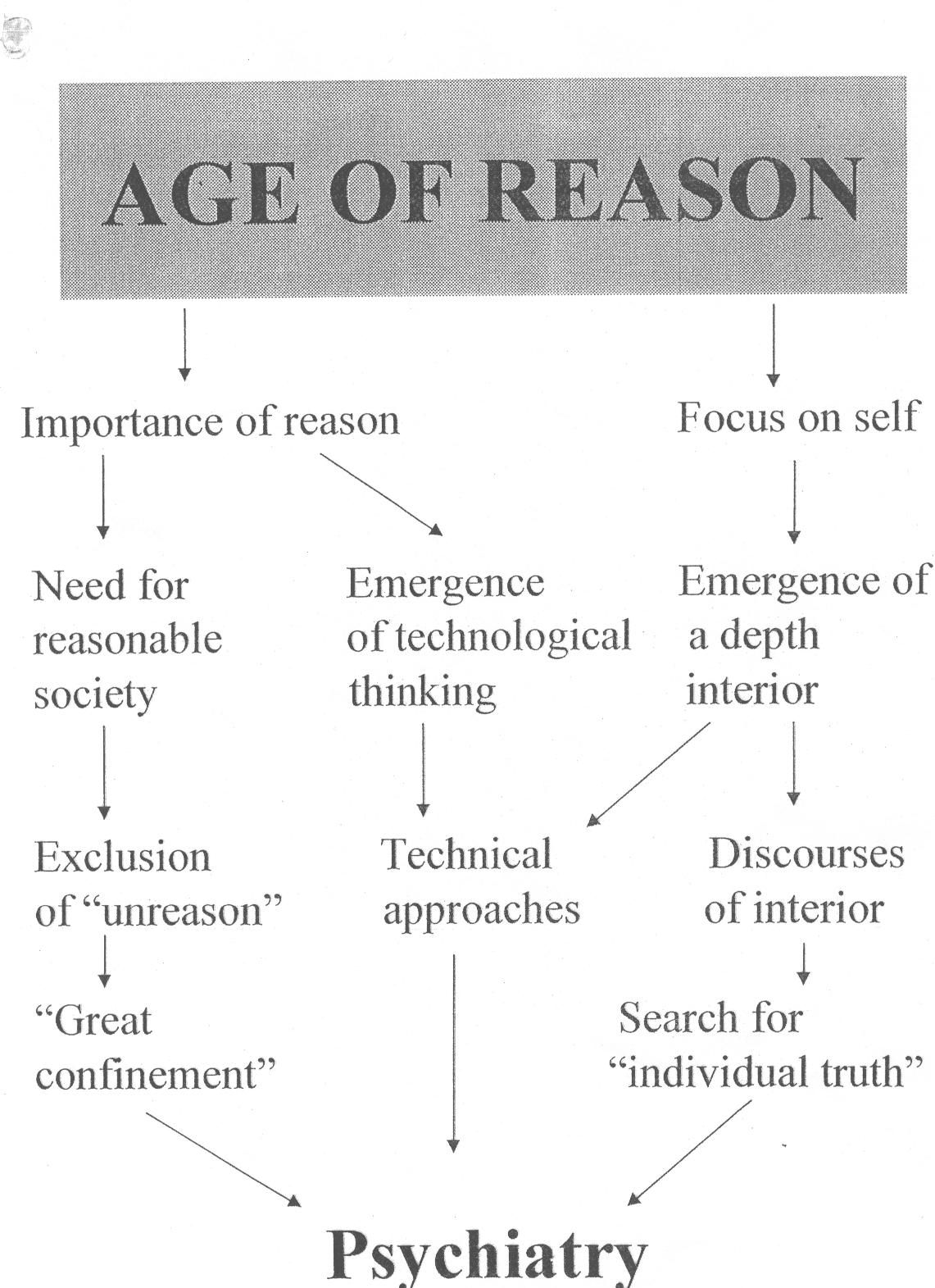

Figure 1

In Fig.1 I have tried to capture the ways in which the cultural transformations of the age of reason led directly to the emergence of psychiatry. On the one hand we see the concern with reason leading to confinement, compulsion and coercion in the practical management of people who were deemed to be 'unreasonable'. We also see this concern with reason leading to a belief in science and the technical ordering of our lives and problems. The so-called human sciences: psychology, sociology, economics, anthropology were very much the products of this outlook. They began to replace the religious and aesthetic orientation of the medieval and renaissance world-view. The doctors who ran the asylums of the 19th century struggled to legitimize their power and prestige by asserting the scientific and medical nature of their theories and treatments. The concern with the interior opened up a territory where 'new discoveries' could be made. Freud, for example, is often portrayed in the guise of an 'explorer of the mind', a bit like Columbus sailing off to unknown and dangerous lands in search of new truths. My argument is that without these cultural developments there would have been no psychiatry.

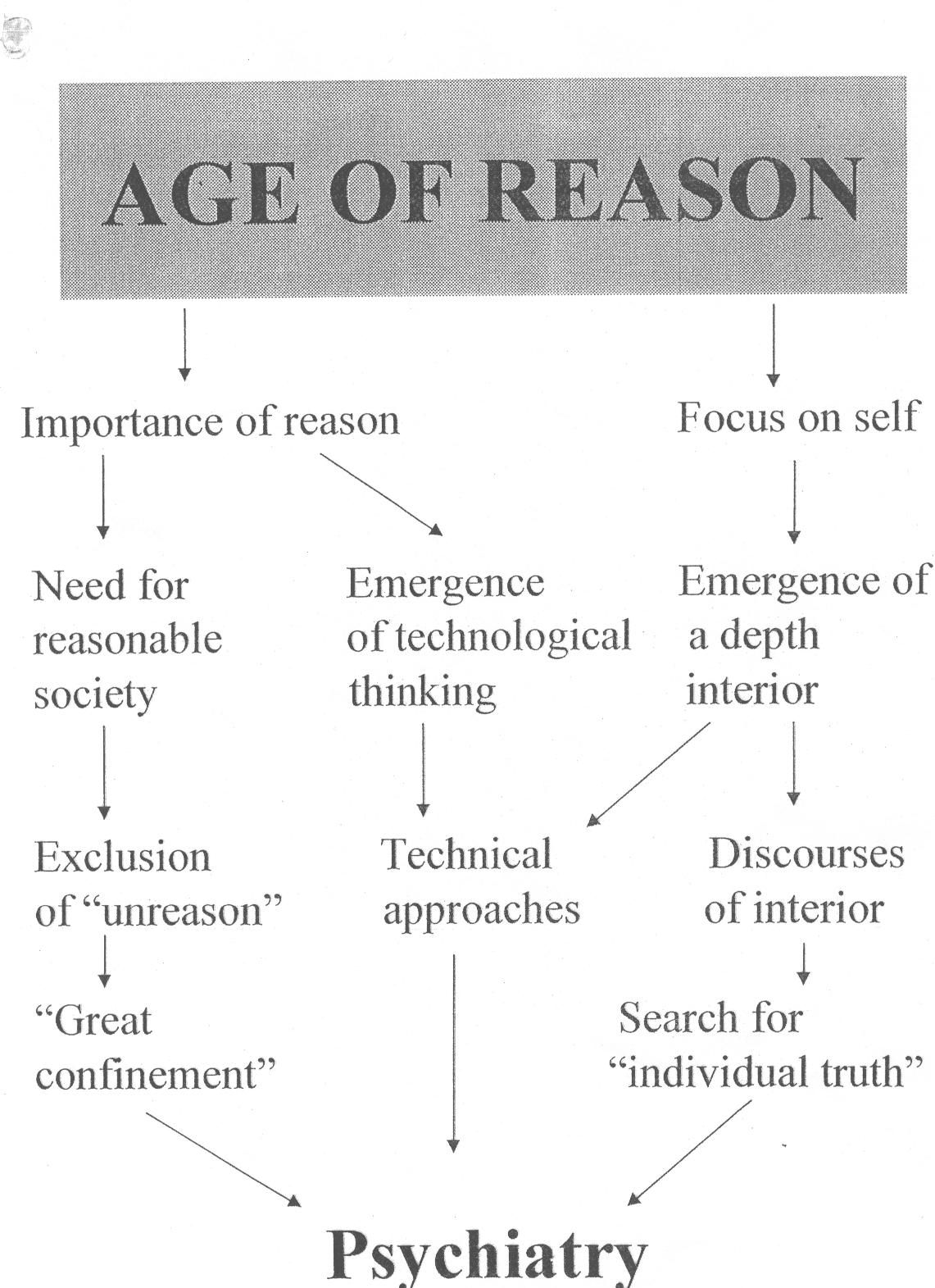

Twentieth century psychiatry concerned itself with an extension and a refinement of this Enlightenment, or modernist, agenda. Its understanding of distress and madness has become even more focused on individuals. It continues to assert a Cartesian understanding of the mind as something separate from the world around it. It continues to seek a separation of mental phenomena from background contexts. Psychosis and emotional distress are defined in terms of disordered individual experience. Social and cultural factors are, at best, secondary, and may or may not be taken into account. This is partly because most psychiatric encounters occur in hospitals and clinics, with a therapeutic focus on the individual, with drugs or psychotherapy. It is also because biological, behavioural, cognitive and psychodynamic approaches share a conceptual and therapeutic focus on the individual self.

The technological orientation of psychiatry has also been extended and developed in the 20th century. In many ways the recent 'decade of the brain' represented the culmination of this development. This was centred on the assertion that madness is caused by neurological dysfunction that can be cured by drugs targeted at specific neuroreceptors. Simplistic and incredible as this might be, it has now become almost heretical to question this paradigm.

The quest to order distress in a technical idiom can also be seen in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM), which defines over 300 mental illnesses, the majority 'identified' in the past twenty years. This has had a powerful effect on psychiatry and psychology but has also extended the reach of this 'technicalisation' of human problems way beyond the traditional boundaries of psychiatric practice. In their book Making Us Crazy. DSM: The Psychiatric Bible and the Creation of Mental Disorders the American writers, Kutchins and Kirk remark:

"DSM is a guidebook that tells us how we should think about manifestations of sadness and anxiety, sexual activities, alcohol and substance abuse, and many other behaviours. Consequently, the categories created for DSM reorient our thinking about important social matters and affect our social institutions" (Kutchins and Kirk, 1999, p. 11)

When it comes to the third dimension of modernist psychiatry, its coercive nature, we have seen how the links between social exclusion, incarceration and psychiatry were forged in the Enlightenment era. In the 20th century, psychiatry's promise to control madness through medical science resonated with the social acceptance of the role of technical expertise. Substantial power was invested in the profession through mental health legislation, which granted psychiatrists the right and responsibility to detain patients and to force them to take powerful drugs, or undergo ECT. Psychopathology and psychiatric nosology became the legitimate framework for these interventions. Despite the enormity of this power, the coercive facet of psychiatry was rarely discussed inside the profession until recently. Psychiatrists are generally keen to downplay the differences between their work and that of their medical colleagues. This emerges in contemporary writing about both stigma and mental health legislation, in which psychiatrists seek to assert the equivalence of psychiatric and medical illness. Ignoring the fact that psychiatry has a particular coercive dimension will not help the credibility of the discipline or ease the stigma of mental illness. Patients and the public know that, unlike schizophrenia, a diagnosis of diabetes cannot result in them being sectioned.

CHALLENGES TO MODERNIST PSYCHIATRY

I believe that a mental health system based on this agenda from the Enlightenment is no longer tenable. We are confronted with a number of challenges that mean a radical rethinking of our guiding assumptions and orientations is needed.

1. First there are (what I shall call) postmodern challenges to the concept of Enlightenment itself. Postmodern thought does not reject the project of Enlightenment but argues that we need to see its downside as well as its positive aspects. It means questioning simple notions of progress and advancement and being aware that science can silence as well as liberate.

2. Psychiatry is also challenged by the cultural shift away from modernism. We now live in an era where there is a greater questioning of scientific expertise and authority. This is seen clearly in the ongoing battle over GM (genetically modified) crops and foods. As we move to the 21st century it is also apparent that as a society we are becoming more comfortable with the notion that perspectives on reality can all have a validity of their own. We are able to live with the idea that there are many different ways of ordering the world, many different paths to the truth and many different ways of thinking about such things as spirituality, health and healing. This is evidenced by the turn to alternative medicine. A recent survey revealed that 20% of GPs in this country practice some form of alternative or complimentary medicine.

3. Perhaps of greatest importance is the rise of the user movement in the past ten years. Users of psychiatry challenge not only the service provision in mental health but also the theories of psychiatry itself. While similar to other users of medicine the challenges presented to psychiatry by service users are more substantial. While patients complain about waiting lists, professional attitudes and poor communication, few would question the enterprise of medicine itself. By contrast, psychiatry has always been thus challenged. Indeed, the concept of mental illness has been described as a myth. It is hard to imagine the emergence of 'anti-paediatrics' or 'critical anaesthetics'; yet anti-psychiatry and critical psychiatry are well-established, influential movements. One of the most influential groups of British mental health service users was called ‘Survivors Speak Out'.

4. Current government policies : Government policies are beginning to change the ethos of mental health care in Britain. The new commitment to tackling the links between poverty, unemployment, and mental illness have led to policies that focus on disadvantage and social exclusion. These emphasise the importance of contexts, values and partnerships, which are made explicit in the National Service Framework for Mental Health. This raises an agenda that is potentially in conflict with biomedical psychiatry. In a nutshell, this government (and the society it represents) is asking for a very different kind of psychiatry, and a new deal between professionals and service users.

These developments raise a series of questions which, I believe, can no longer be ignored :

* If psychiatry is the product of the institution, should we not question its ability to determine the nature of post-institutional care?

* Can we imagine a different relationship between medicine and madness; different, that is, from that forged in the asylums of a previous age?

* If psychiatry is the product of a culture preoccupied with rationality and the individual self, what sort of mental health care is appropriate in the post-modern world in which such preoccupations are waning?

* How appropriate is Western psychiatry for cultural groups who value a spiritual ordering of the world, and an ethical emphasis on the importance of family and community?

* How can we uncouple mental health care from the agenda of social exclusion, coercion and control to which it became bound in the last two centuries?

I believe that if we do not face up to these questions we are in danger of replicating the problems of institutional care in our community services. Indeed, there is evidence that this has already begun to happen with a number of assertive outreach services in the United States. Relying on the traditional medical approach to understanding madness and distress, these services often see the administration of medication as their most important goal. Other service elements are used to engage users but only in a bid to ensure compliance. As a result, many users have complained that they experience these services as being as oppressive as traditional hospital psychiatry and have begun to campaign against them (Oaks, 1998).

For these reasons, postpsychiatry is driven by a contrasting set of goals.

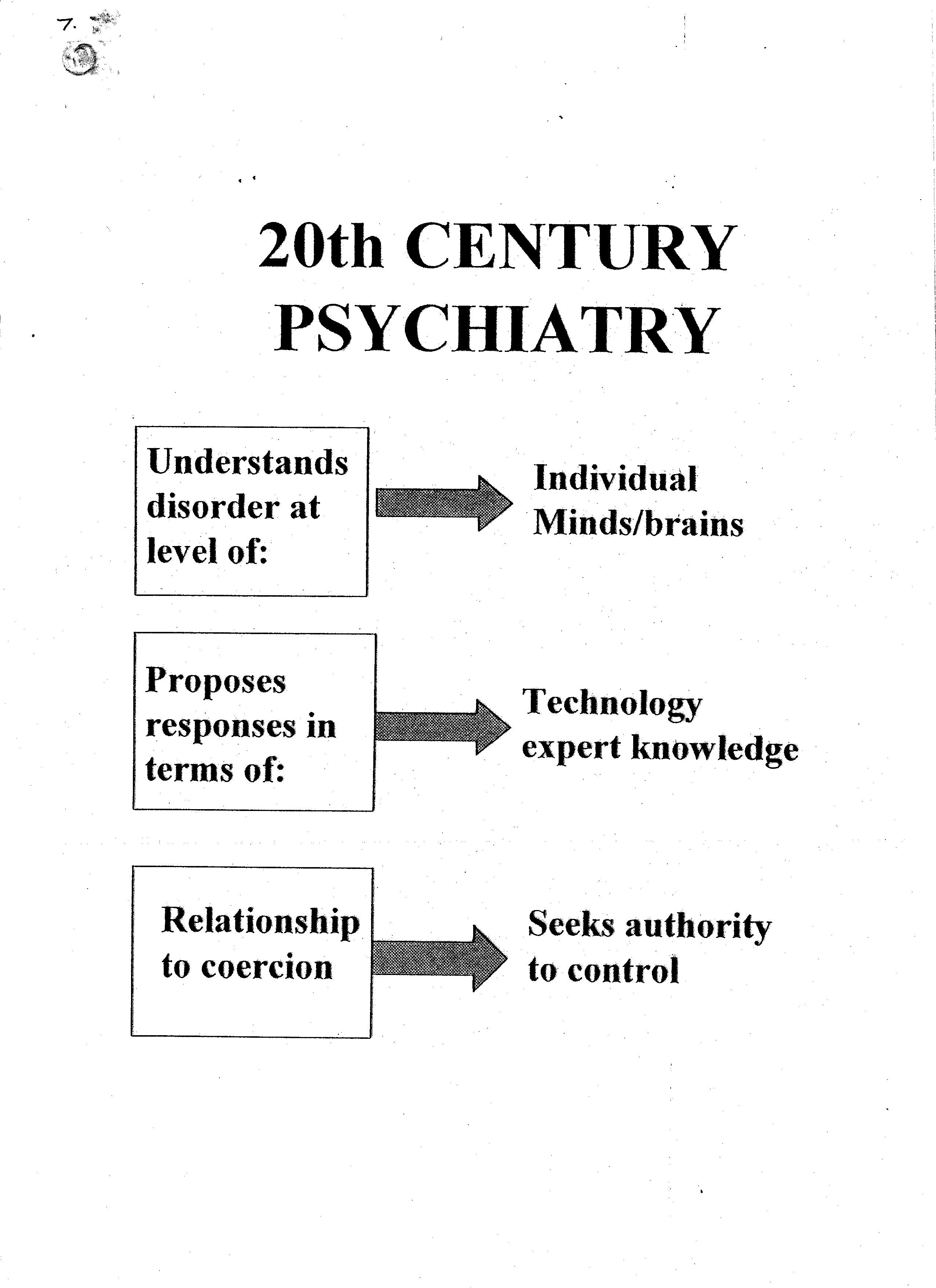

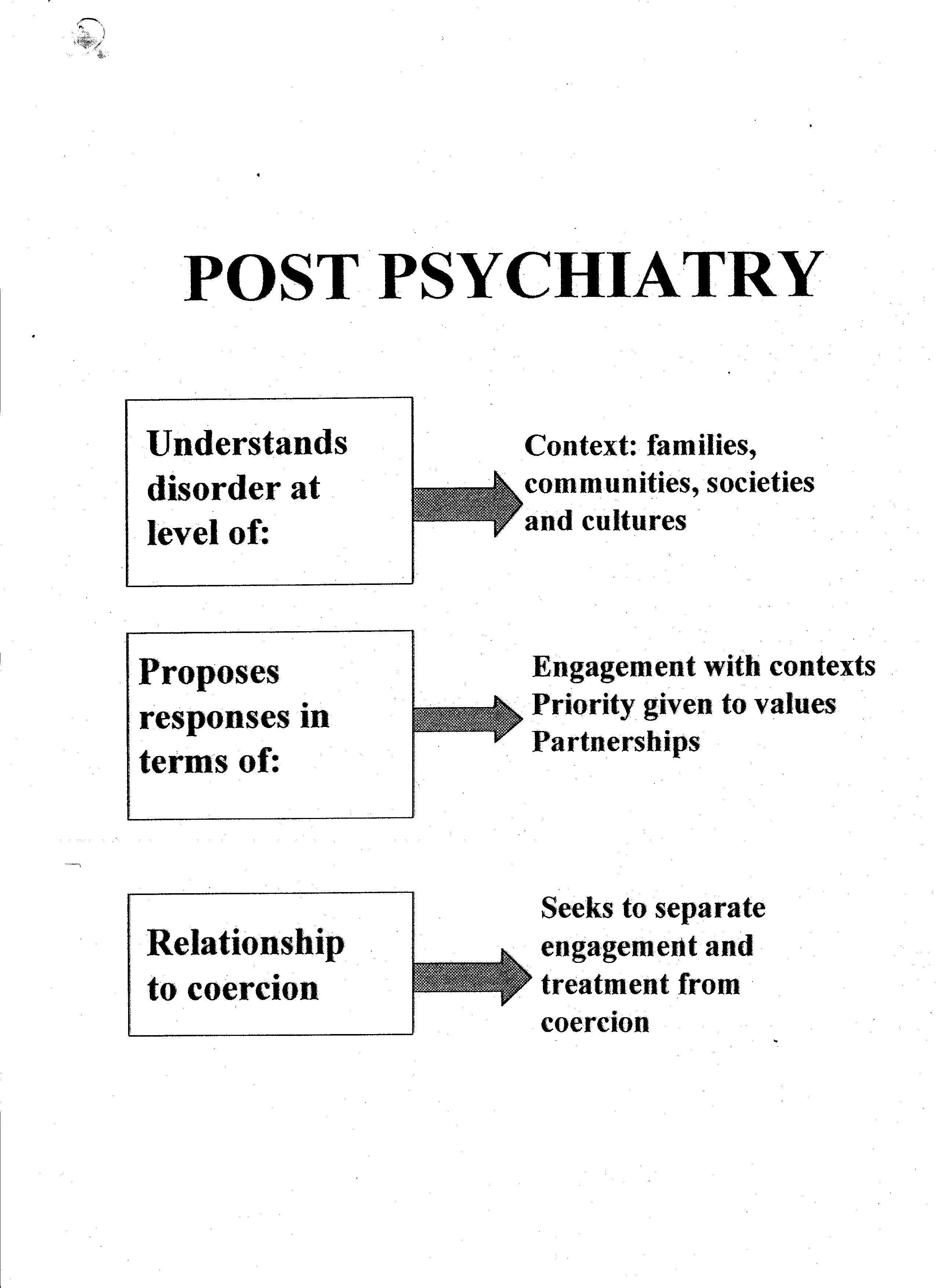

POSTPSYCHIATRY

Postpsychiatry is about a new way of looking at the theory and practice of mental health. It is concerned to frame the difficulties and challenges we face from a different starting point. Unlike anti-psychiatry and previous forms of critical psychiatry it does not, itself, propose new theories about madness but by a deconstruction of psychiatry seeks to open up spaces in which other, alternative, understandings of madness can assume a validity denied them by psychiatry. Crucially, it argues that the voices of service-users and survivors should now be centre-stage. Similarly, postpsychiatry seeks to distance itself from the therapeutic implications of anti-psychiatry. It does not propose any new form of therapy to replace the medical techniques of psychiatry. Anti-psychiatry, especially as developed by R.D. Laing, proposed a modified version of psychoanalysis (based largely on existential philosophy) as an alternative to psychiatry. Others, writing under the heading of 'critical psychiatry', such as Ingleby and Kovel, also looked to different versions of psychoanalysis to frame their theories and practice (Ingleby, 1980). Postpsychiatry sees the theories of Freud and other analysts as part of the problem, not the solution!

To use a spatial metaphor, postpsychiatry is not a place, a set of fixed ideas and beliefs. Instead, it is more like a set of orientations which together can help us move on from where we are now. It does not to seek to prescribe an end point and does not argue that there are 'right' and 'wrong' ways of tackling madness.

Both theoretically and practically a postpsychiatry perspective emphasises the importance of contexts. An understanding of social, political and cultural realities, should be central to our understanding of madness. A context-centered approach acknowledges the importance of empirical knowledge in understanding the effects of social factors on individual experience, but it also engages with knowledge from non-Cartesian models of mind, such as those inspired by the philosophers Wittgenstein and Heidegger and the Russian psychologist Vygotsky. I use the term 'hermeneutic' for such knowledge, because priority is given to meaning and interpretation. Events, reactions and social networks are not conceptualised as separate items which can be analysed and measured in isolation, but are instead understood as bound together in a web of meaningful connections which can be explored and illuminated, whilst defying simple causal explanation.

We also believe that, in practical clinical work, mental health interventions do not have to be based on an individualistic framework centered on medical diagnosis and treatment. The Hearing Voices Network offers a good example of how very different ways of providing support can be developed. This does not negate the importance of a biological perspective but it refuses to privilege this approach and also views it as being based on a particular set of assumptions, which themselves are derived from a particular context.

Secondly, postpsychiatry seeks to problematise the ever-increasing tendency to medicalise and technicalise our lives and our problems. ‘Clinical effectiveness' and 'evidence-based practice'; the idea that science should guide clinical practice, currently dominate medicine. Psychiatry has embraced this agenda in the quest for solutions to its current difficulties. The problem is that clinical effectiveness downplays the importance of values in research and practice. All medical practice involves a certain amount of negotiation about assumptions and values. However, because psychiatry is primarily concerned with beliefs, moods, relationships and behaviours this negotiation actually constitutes the bulk of its clinical endeavours. Recent work by medical anthropologists and philosophers, has pointed to the values and assumptions which underpin psychiatric classification.

While this is an issue for all mental health work the dangers of ignoring these questions is most apparent in the problematic encounter between psychiatry and non-European populations, both within Europe and elsewhere. In Bradford, we work with a large number of immigrant communities. The Bradford Home Treatment Service (Bracken, 2001) attempts to keep values to the fore and strives to avoid Eurocentric notions of dysfunction and healing. Whilst recognizing the pain and suffering involved in madness, the team avoids the assumption that madness is meaningless. It has also developed a number of ways in which service users can be involved in shaping the culture and values of the team.

Thirdly, postpsychiatry seeks to separate issues of care and treatment from the process of coercion. The debate about the new Mental Health Act in Britain offers an opportunity to rethink the relationship between medicine and madness. As I have discussed already, many individual service users and service-user organizations question the 'medical model' and are therefore outraged that this provides the framework for coercive care. This is not to say that society should never remove a person's liberty on account of mental disorder. However, by challenging the notion that psychiatric theory is neutral, objective and disinterested, postpsychiatry weakens the case for medical control of the process. Perhaps, doctors should be able to apply for detention (alongside other individuals and groups), but not make the decision to detain someone. In addition, the principle of reciprocity means that legislation must include safeguards such as advocacy and advance directives.

CONCLUSION

In the past psychiatry has reacted defensively to challenges and, throughout the 20th century, has asserted its medical identity. However, while the discipline survived the anti-psychiatry of the 1960s, as we have seen, fundamental questions about its legitimacy remain. The so-called ‘failure’ of community care and the British government’s response (in the form of the National Service Framework) make it essential that we critically re-examine psychiatric frameworks. In this chapter I have sought to develop a critique of the modernist agenda in psychiatry, and to outline the basic tenets of postpsychiatry.

Psychiatry, like medicine, will have to adapt to 'postmodern environment' in which we now live and to the reality of the user movement. This is not going to go away. Indeed, in my opinion it will go from strength to strength. In many ways it’s a case of: you ain't seen nothing yet!!!

Twenty years ago homosexuality was still defined as a disease by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual in the US. The movement for Gay Rights was small and easily dismissed. The idea that in the future there would be TV programs made for gay people by gay people or that a number of cabinet ministers would be openly gay would have been dismissed as laughable. We don't know at this stage how the user movement will develop, but develop and expand it will.

Postpsychiatry seeks to 'democratise' the field of mental health by linking progressive service development to a debate about contexts, values and partnerships. I believe that the advent of postmodernity offers an exciting challenge for doctors and other professionals involved in this area and represents an opportunity to rethink our roles and responsibilities.

I look forward to a situation where experiences such as hearing voices, depression, fearfulness, withdrawal and self-harm are no longer conceptualised as purely medical issues. Contrary to the prevailing approach within psychiatry I believe that we will reduce the stigma of madness and distress only by demedicalising the field.

However, giving up the frameworks and models we have become used to is not without its difficulties. Framing our lives and difficulties in a medical way has its immediate advantages. But then struggle for democracy has never been easy.

References

Bracken, P. (2001) The radical possibilities of home treatment: postpsychiatry in action. In : Acute Mental Health Care in the Community: Intensive Home Treatment. Edited by N. Brimblecombe. London : Whurr Publishers.

Bracken, P. and Thomas, P. (2001) Postpsychiatry : a new direction in mental health. British Medical Journal, 322: 724-727

Foucault, M. (1967) Madness and Civilization : A History of Insanity in the Age of Reason. Translated by R. Howard. London : Tavistock.

Ingleby, D. (1980) Critical Psychiatry. New York : Pantheon Books.

Kutchins, H. and Kirk, S. (1999) Making Us Crazy. DSM: The Psychiatric Bible and the Creation of Mental Disorders. London: Constable.

Oaks, (1998) A new proposal to Congress may mean daily psychiatric drug deliveries to your doorstep. Dendron, 41/42, 4-7. (The journal Dendron is published by the Support Coalition International which is based in Oregon, U.S.A.)

Porter, R. (1987) A Social History of Madness. Stories of the Insane. London : Weidenfeld and Nicolson.